Richard Andrews recounts events around the proclamation of independence in PNG in 1975.

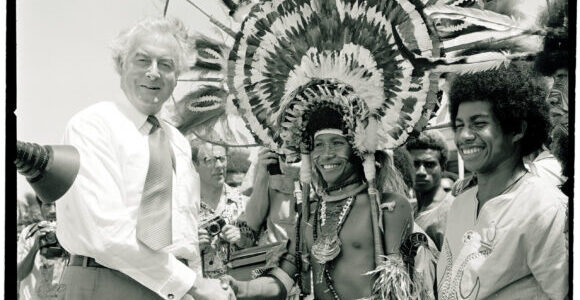

Former Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in Port Moresby for the declaration of independence in 1975.

A century of colonialism ended on September 16, 1975, when Papua New Guinea gained independence from Australia, to become a constitutional monarchy and member of the British Commonwealth. At sunset on September 15, 1975, the Australian flag was lowered at the Sir Hubert Murray Stadium in Port Moresby, and the following day the PNG flag was raised for the first time.

“We are lowering it, not tearing it down,” said Governor-General Sir John Guise about the Australian emblem – emphasising PNG’s peaceful transition to independence. “We are raising our own flag, a flag that represents our identity and aspirations.”

At one minute past midnight on September 16, Sir John gave the proclamation of independence, followed by the PNG national anthem and a 101-gun salute from the Royal Australian Navy. Fireworks lit up the sky and celebrations continued through the night and into the following days.

Thousands attended the main ceremony on September 16, many in traditional dress, with brightly coloured body paint, feathers, grass skirts, shell jewellery, and headdresses representing the diversity of PNG’s 600 islands and more than 800 languages.

Officiating at the main ceremony on the capital’s Independence Hill were His Royal Highness Prince Charles, Prince of Wales (representing Queen Elizabeth II, the British monarch); Chief Minister of Papua New Guinea, Michael Somare, the country’s ‘founding father’, first Prime Minister and Grand Chief; Sir John Guise, Governor-General of Papua New Guinea; Australian Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam; and Sir John Kerr, Governor-General of Australia.

In a stirring and emotional speech on the morning of the 16th, Somare emphasised the historical significance of the day and the importance of national unity.

“I speak to you today as your first Prime Minister. We are now masters of our own destiny,” he announced. “As a united people, we will achieve our goals with the stability of our background to support us, and the richness of the earth to provide for us.”

Unlike many emerging countries in the postcolonial period of the 1950s and 1960s, PNG, as a Trust Territory administered by Australia, escaped the need for an ugly fight to achieve its own destiny.

Like the Governor-General, Somare acknowledged the country’s good fortune for a peaceful transition in a turbulent era.

“We have been lucky because we have reached full nationhood without the fighting and bloodshed that has been experienced by many other former colonies,” observed Somare.

In that spirit, Prince Charles, speaking on behalf of the Queen, welcomed PNG into the Commonwealth and passed on her “regards and affection.”

In his speech, Australia’s Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, emphasised the benefit of independence for both countries.

“Today Australia, herself once a group of colonies, has ended the role as a colonial power imposed upon her by an irony of history. Australia could never be truly free until Papua New Guinea was truly free. In a very real sense, this is a day of liberation for Australia as much as for Papua New Guinea.”

However, the historical event was not without its critics during the lead-up to the day. PNG’s Post Courier reported heated debate in different areas and arguments by some local leaders that independence “was not the result of national consensus.”

Objection took various forms. According to the paper, “the rainmaker of (separatist movement) Papua Besena tried to ruin Independence Day but failed to maintain unseasonable squalls just before the ceremonies started.”

This attempt might explain a puzzling, off-topic comment about the weather, made by Prince Charles. A grainy news video shows him saying, in halting Tok Pisin: “Asde ren bagarap mi, nau mi orait.” (“Yesterday the rain ruined my day, but now I’m alright.”)

New Guinea’s exposure to English and other colonial powers probably dates to the 16th century. Portuguese explorer Jorge de Menezes accidentally came upon the island and is credited with naming it ‘Papua’, supposedly after a Malay word for frizzy hair.

According to a preferred theory, the term ‘papua’ may have meant ‘lands below the sunset’ in the Biak language.

The Spaniard Yñigo Ortiz de Retez applied the term ‘New Guinea’ to the island in 1545 because of a perceived resemblance between the island’s inhabitants and those found on the slave-trading African Guinea coast.

A complex interplay of European powers followed over the years. The northern part became German New Guinea in the 19th century, while the southern part, including coastal regions, was a British protectorate.

Later it became the Territory of Papua under Australian administration. Following World War 1, Australia took control of German New Guinea as a League of Nations mandate. After the Japanese surrender in World War 2, both Papua and New Guinea were combined under Australian administration.

Whitlam had long been unhappy with this arrangement. Even as leader of Australia’s Opposition, he’d described Australia’s colonial rule over PNG as “wrong and unnatural” given Australia’s own history as a penal colony.

In 1969, when visiting Wewak, he was confronted by a young secretary from a local trade union who asked boldly when Australia would give PNG its independence. Whitlam responded: “How about tomorrow?”

Six years after that fateful meeting, Michael Somare became PNG’s first Prime Minister.

This article was first published in the August-October 2025 issue of Paradise, the in-flight magazine of Air Niugini.

Speak Your Mind