The Papua New Guinea authorities should allow the currency to fall to its market level to make foreign bond raisings less risky says economist Rohan Fox. He tells Business Advantage PNG that domestic banks are reaching the limits of their capacity to take on government debt, which is increasing the pressure to raise capital internationally.

Rohan Fox Credit: Rohan Fox

Fox is Visiting Lecturer and Research Fellow at the University of Papua New Guinea’s Division of Economics. His comments relate to an intense debate in the country about how PNG can solve its foreign exchange crisis, which is having an adverse effect on many businesses.

The Governor of the Bank of Papua New Guinea, Loi Bakani, is on the record questioning claims that allowing the kina to weaken—at the moment the Bank manages the level of the currency—will solve the foreign exchange problem.

Bakani also stated, however, that he is ‘determined’ to get more foreign exchange in. The government is reported to be looking to raise capital with a sovereign bond.

It is here that Fox’s argument comes in. He argues that if the kina is allowed to weaken, it would reduce some of the risks associated with borrowing internationally.

Supply and demand

To understand the argument, consider that when a currency falls, the cost of its foreign borrowings rise. If, for example, $US1 billion is raised when the kina is trading at US 0.30 then the debt at the time will translate into K3.3 billion. But if the kina later falls to US 0.20, then the local currency debt will rise to K5 billion.

‘If the kina depreciates now, then the government will get substantially more kina when it converts the foreign exchange from the bond,’ says Fox. ‘This removes substantial foreign exchange risk.

‘The banks have reached their specified limits to the previous offerings of government debt.’

Fox acknowledges that allowing the currency to weaken will ‘sadly cause hardship for some’ adding that it is ‘not a panacea’. But he says allowing supply and demand to set the exchange rate—with the implication that the kina will weaken—’is one of the few clear policy levers available to the government.’

Banks

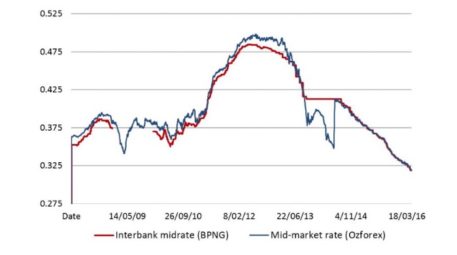

Kina-US$ exchange rate. Source: Devpolicy blog

The need to get in more foreign exchange is not the only reason pressure is rising to raise money internationally. The ability of domestic banks to fund the government’s debt is also coming under question.

Fox says the domestic banks are reaching the limits of their capacity to take on more government debt. Consequently, they have not been taking up ‘normal’ bond offerings from the government.

‘The commercial banks may not disclose their limits for exposure to government bonds at a particular price, but they “reveal” their overall limits as a sector when government securities stop getting bought by banks.’

Fox says this has affected the way the Bank of Papua New Guinea has offered Treasury Bills to the market, increasing the costs.

‘To gain access to further credit from domestic banks, they have to make the terms more amenable.

A sovereign bond is likely to have a lower interest rate than debt raised in PNG.

‘One way to do this is to reduce the terms of the bills. This makes them a different type of risk for domestic banks to be exposed to. But it is more costly administratively for government.’

Interest rates

There may be a further reason for the PNG authorities to look internationally. Global interest rates are at historic lows, especially in the developed world.

Fox says a sovereign bond is likely to have a lower interest rate than debt raised in PNG. ‘The interest cost of their five year US 500 million bond was 10.9 per cent per annum, which is cheaper than the latest costs of PNG borrowing domestically for five years which were 11.8 per cent per annum.’

‘I don’t envy the decisions the PNG authorities have to make.’

‘But it does have extra costs in terms of commission to banks that organise the bond (likely to be in the range of 2-4 per cent).’

Decisions

Fox acknowledges that there are no easy solutions. ‘There is no doubt that it is very tricky, and I don’t envy the decisions the PNG authorities have to make.

‘The decisions that may be the best economically down the track, are not the same as the ones that are the best politically in the short-term.

‘A more competitive exchange rate would be one policy that I believe would be positive overall. There is recent empirical evidence which says that resource exporting countries with flexible exchange rates have better outcomes and faster recovery in terms of GDP growth and government expenditure, than countries with less flexible regimes.’

Speak Your Mind